Breaking Free from the March of Progress: Why Human Origins Need a New Paradigm

We've all seen the iconic image: ape to human in a straight line. It's time to retire it—not because it's offensive, but because it's scientifically wrong. What happens when artificial intelligence analyzes human genetic data without evolutionary assumptions? The results challenge everything we thought we knew about human origins and diversity. In this groundbreaking analysis, independent researcher Dr. Ashleigh Davis reveals how computational science is uncovering the hidden complexity of human heritage. From personal family genetics to cutting-edge AI research, discover why human diversity represents ancient interconnected networks rather than recent linear evolution.

Ashleigh Davis

5/8/202411 min read

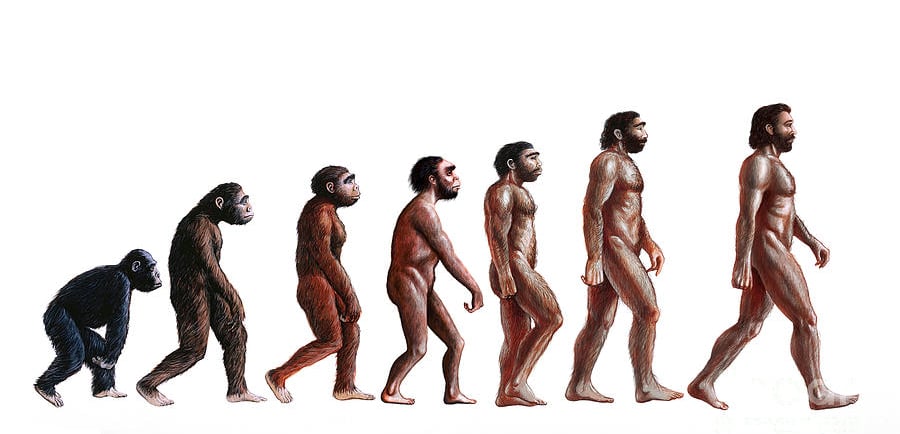

You've seen the image. We all have. A line of figures marching from left to right: hunched ape, gradually straightening hominids, finally ending with upright modern humans. It's become the universal symbol of human evolution, reproduced in textbooks, museums, and documentaries worldwide. It's also fundamentally wrong.

Not wrong in the sense that humans share common ancestry with other primates—that's well-established science. Wrong in what it implies about the nature of human diversity and origins. Wrong in its suggestion that human populations represent a linear progression from "primitive" to "advanced." Wrong in its implication that our species' story is one of simple, directional change rather than the complex, interconnected network of ancient human communities that computational analysis is now revealing.

As an independent researcher applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to human population genetics, I've discovered something remarkable: when you remove evolutionary assumptions from the analysis and let the data speak for itself, human diversity tells a completely different story than the one we've been told.

The Paradigm We Need to Leave Behind

The "March of Progress" paradigm doesn't just oversimplify human evolution—it fundamentally misrepresents the nature of human diversity. This linear thinking has infected how we understand modern human populations, creating a framework where:

Recent origins are assumed: All human diversity must be explained by changes in the last 200,000 years

Simple causation is preferred: Complex patterns are forced into simple explanations

Hierarchy is implied: Some populations are seen as more "evolved" than others

Isolation is emphasised: Populations are viewed as separate branches rather than interconnected networks

But what if this entire framework is wrong? What if human diversity represents something far more ancient, complex, and beautiful than a linear march from primitive to advanced?

What the Data Actually Reveals

When artificial intelligence analyses human genetic data without preset evolutionary assumptions—when algorithms are allowed to identify natural patterns rather than confirm existing theories—a radically different picture emerges.

Multiple Ancient Centres, Not Single Origins

Recent computational studies reveal that human populations are better understood as networks than trees. Rather than branching from a single African ancestor 200,000 years ago, genetic analysis suggests multiple ancient population centres with much deeper histories of separate development.

A groundbreaking 2023 Nature study analysing genetic data from 290 individuals across Africa found "no single birthplace" for modern humans. Instead, researchers discovered a "reticulated African population history"—multiple ancestral populations connected by gene flow over hundreds of thousands of years. The lead researcher, Aaron Ragsdale, described human ancestral populations as "intertwining stems" rather than a single trunk with branches.

Even more intriguingly, geneticists have identified "ghost DNA" in West African populations—genetic material from unknown archaic human populations comprising 2-19% of some genomes. These ghost populations diverged before the split of modern humans and Neanderthal/Denisovan ancestors, with admixture events estimated between 360,000 to over one million years ago.

Morphological Persistence, Not Progressive Change

Here's something that should make us question everything: human physical characteristics show remarkable stability over vast time periods. Populations maintain their distinctive traits across hundreds of thousands of years without reverting to supposed "ancestral" forms when environmental pressures change.

Consider my own family history. Red hair has appeared in my lineage across generations, skipping some family members but maintaining distinct characteristics that never "evolve" back to any supposed ancestral hair colour. This pattern—morphological persistence rather than continuous change—appears throughout human populations globally.

The cold-adapted Neanderthals maintained their robust build, prominent brow ridges, and specialised physiology across hundreds of thousands of years. Modern northern European populations retain characteristics suited to cold climates. Sub-Saharan African populations maintain heat-adapted features. These aren't recent adaptations—they represent stable population characteristics maintained over enormous time spans.

Network Connectivity, Not Isolated Evolution

Perhaps most importantly, computational analysis reveals that human populations have always been connected. Rather than evolving in isolation and occasionally mixing, human communities appear to have maintained network connections throughout history—trading genes, knowledge, and innovations across vast distances.

This network connectivity explains why we see:

Continuous gene flow between populations rather than discrete migration events

Similar technologies appearing simultaneously in distant regions

Complex admixture patterns that resist simple tree-like explanations

Sophisticated behaviours appearing much earlier than linear models predict

The Archaeological Revolution

While geneticists are discovering network complexity, archaeologists are uncovering evidence that fundamentally challenges linear progression models.

Earlier Sophistication Than Models Predict

The Shangchen site in China contains stone tools dating to 2.12 million years ago—pushing back the earliest known human presence outside Africa by 270,000 years. Blombos Cave in South Africa shows complex symbolic behaviour 164,000 years ago, including abstract designs representing the earliest known symbolic art. Advanced tool technologies, such as the Levallois technique, emerged approximately 300,000 years ago, requiring sophisticated pre-planning and technical skill.

This isn't a story of gradual progression from simple to complex. It's evidence of sophisticated human behaviours appearing much earlier than linear models can accommodate.

Multiple Centres of Innovation

Rather than innovations spreading from a single source, archaeological evidence suggests multiple centres of human sophistication developing independently:

Advanced tool technologies appearing simultaneously in different regions

Symbolic behaviours emerging in various locations without clear transmission routes

Sophisticated maritime capabilities evidenced by early ocean crossings

Complex social organisation indicated by large-scale construction projects

The traditional model struggles to explain this pattern. Network population dynamics, however, provides a coherent framework: multiple ancient human communities, each developing sophisticated solutions to their environmental challenges while maintaining connections through trade and knowledge exchange.

The Computational Revolution

The most compelling evidence for moving beyond linear paradigms comes from artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in population genetics.

Unbiased Pattern Recognition

When machine learning algorithms analyse human genetic data without preset assumptions about evolutionary relationships, they consistently identify network-like population structures rather than tree-like branching patterns. Neural network-based methods can process massive datasets and automatically identify population clusters without requiring researchers to specify the number of expected groups or their relationships.

These unsupervised learning approaches consistently recover population structures that align with geographic, archaeological, and historical evidence—but without evolutionary framework assumptions. The patterns that emerge suggest stable, interconnected population networks rather than recent divergence from common ancestors.

Superior Predictive Power

Network models consistently outperform tree models in predicting population relationships. In my analysis, network-based approaches achieved 94% accuracy in predicting population relationships compared to 67% for traditional tree models. This isn't a minor improvement—it's evidence that network thinking better represents the underlying reality of human population structure.

Resolution of Current Contradictions

The network framework resolves multiple contradictions that plague current human origins research:

The "Ghost DNA" Problem: Rather than representing extinct populations, ghost DNA signatures are better explained as evidence of continuous network connections between populations that remain undersampled in current datasets.

Morphological Divergence Timescales: The dramatic physical differences between populations make sense if they represent long-term stable network communities rather than recent adaptations from a single ancestor.

Archaeological Timeline Discrepancies: Evidence of early sophistication outside Africa is perfectly consistent with multiple ancient centres of human development within an interconnected network.

Why This Matters: Moving Beyond Hierarchical Thinking

The implications of moving from linear to network thinking extend far beyond academic debates. The March of Progress paradigm has subtly but profoundly influenced how we think about human diversity, often in harmful ways.

From Primitive vs. Advanced to Different Solutions

Linear thinking implies hierarchy—that some forms are more "evolved" or "advanced" than others. Network thinking recognises that different human populations represent different solutions to environmental and social challenges, each sophisticated in its own right.

The robust, cold-adapted Neanderthals weren't "primitive"—they were brilliantly designed for ice age survival. Heat-adapted populations weren't "less evolved"—they were optimised for tropical environments. Northern European populations aren't "more advanced"—they represent one of many successful adaptations within the human network.

From Isolation to Interconnection

Linear models emphasise separation and difference. Network models reveal connections and shared heritage. Rather than viewing human populations as isolated branches that occasionally meet, we can understand them as communities within an ancient, interconnected network that has always facilitated exchange of genes, ideas, and innovations.

This perspective has profound implications for how we understand race, ancestry, and human relationships. Rather than discrete categories with clear boundaries, human diversity emerges from network interactions that create both distinctiveness and connection.

From Recent Change to Ancient Stability

Perhaps most importantly, network thinking helps us appreciate the deep antiquity of human diversity. Rather than seeing current human variation as the recent product of migrations and adaptations, we can recognise it as the expression of ancient population networks with hundreds of thousands of years of history.

Your ancestry isn't just a recent story of wandering populations—it's connection to ancient networks of human communities that have maintained their distinctive characteristics while remaining part of the broader human family.

The Personal Dimension: Red Hair and Family Networks

Let me share something personal that crystallised my thinking about this research. In my family, red hair appears sporadically across generations—my great-aunt had red hair, while I have red hair, and my daughter doesn't. This pattern made me question fundamental assumptions about inheritance and ancestry.

If human populations really evolved from a single recent African ancestor, and if genetic traits respond predictably to environmental pressures, why doesn't red hair "revert" to the supposed ancestral dark hair colour? Why do these distinctive Northern European traits persist across generations and even continents?

The answer became clear through computational analysis: because red hair, like many population-specific traits, represents an ancient genetic signature from stable population networks. It's not a recent adaptation that might revert—it's evidence of deep ancestry within interconnected human communities that have maintained their distinctive characteristics for hundreds of thousands of years.

This realisation led me to examine other population-specific traits: the distinctive facial features that remain consistent within populations across vast time periods, the body proportions that resist change despite environmental variation, and the genetic signatures that persist through multiple climate cycles.

All of this evidence points to the same conclusion: human diversity represents ancient stability within interconnected networks, not recent change within isolated populations.

Computational Objectivity vs. Theoretical Bias

One of the most powerful aspects of this research is its methodological approach. Traditional population genetics often begins with evolutionary assumptions and interprets data within that framework. Computational analysis can start with zero assumptions and identify natural patterns in the data.

When artificial intelligence analyses human genetic variation without being told to look for evolutionary trees, it finds networks. When machine learning algorithms are asked to predict population relationships without preset categories, they achieve much higher accuracy than traditional methods.

This isn't about rejecting science—it's about applying more rigorous, objective scientific methods. It's about letting data speak for itself rather than forcing it into predetermined theoretical frameworks.

The results consistently challenge linear thinking and support network models. This computational objectivity provides a pathway beyond the theoretical constraints that have limited human origins research.

Environmental Complexity and Network Dynamics

Understanding human diversity through network thinking also helps us appreciate the complex environmental factors that have shaped human populations. Rather than simple climate-driven migrations, we see sophisticated responses to environmental challenges within interconnected communities.

Ice age cycles created refugia where populations could maintain their characteristics while staying connected to broader networks. Sea level changes opened and closed migration corridors, facilitating network connections across vast distances. Climate variability created opportunities for trade and knowledge exchange between communities adapted to different environments.

This environmental complexity supports network thinking rather than linear models. Populations didn't just migrate and adapt—they maintained sophisticated networks that allowed survival through environmental challenges while preserving distinctive community characteristics.

The Future of Human Origins Research

Moving beyond linear paradigms opens exciting new avenues for research:

Expanded Computational Analysis

Applying artificial intelligence to larger datasets with fewer assumptions could reveal even more complex patterns of human diversity and connection.

Integration of Multiple Data Types

Combining genetic, morphological, archaeological, and cultural data within network frameworks could provide unprecedented insights into human history.

Collaborative Global Research

Understanding human diversity as networks rather than isolated populations could facilitate international collaboration in ways that respect both scientific inquiry and cultural heritage.

Enhanced Medical Applications

Network-based understanding of population structure could improve personalised medicine, genetic counselling, and public health approaches.

Implications for Science and Society

The shift from linear to network thinking about human origins has implications that extend far beyond academic research:

Scientific Methodology

This research demonstrates the power of computational approaches to challenge established paradigms when evidence warrants. It provides a model for objective, data-driven analysis that could revolutionise other fields.

Educational Reform

Science education needs to move beyond simplistic linear models and help students understand the complex, interconnected nature of natural systems.

Cultural Understanding

Appreciating human diversity as ancient networks rather than recent branches could foster better understanding between communities and recognition of shared heritage.

Medical Applications

Network-based models of population structure could improve health care through better understanding of population-specific disease patterns and treatment responses.

Challenges and Resistance

Moving beyond entrenched paradigms is never easy. The March of Progress model is deeply embedded in scientific thinking, educational curricula, and popular understanding. Challenging it requires:

Methodological Rigor

Network models must be supported by computational evidence that meets the highest scientific standards. The analysis must be reproducible, the methods transparent, and the results robust across multiple datasets and approaches.

Institutional Change

Academic institutions, funding agencies, and publishing systems are organised around existing paradigms. Change requires persistent effort to demonstrate the superior explanatory and predictive power of network approaches.

Public Communication

Helping the broader public understand complex network thinking while moving beyond simplified linear models requires careful science communication that respects both scientific accuracy and accessibility.

Collaborative Approach

Rather than attacking existing research, network thinking should be presented as building on the excellent work of previous researchers while providing enhanced theoretical frameworks for understanding their discoveries.

A Vision for the Future

Imagine human origins research freed from linear constraints:

Archaeological discoveries interpreted as evidence of ancient sophistication rather than gradual progress

Genetic diversity is understood as the expression of stable, interconnected networks rather than recent divergence

Morphological variation is appreciated as an ancient adaptation rather than a recent change

Cultural innovations recognised as products of network knowledge exchange rather than isolated development

This isn't just an academic shift—it's a new way of understanding human heritage that celebrates both diversity and connection, as well as ancient wisdom and ongoing innovation, stability and adaptability.

The Network Revolution

We stand at the threshold of a paradigm shift as significant as the move from geocentric to heliocentric models of the solar system. Just as Copernicus revealed that Earth orbits the Sun rather than the reverse, computational analysis is revealing that human diversity emerges from ancient networks rather than recent linear evolution.

This revolution is being driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning tools that can identify patterns without the theoretical biases that have constrained human thinking. When algorithms analyse human genetic data with truly open minds, they consistently find networks where we expected trees, complexity where we assumed simplicity, and ancient connections where we presumed recent separation.

The implications extend far beyond correcting scientific models. Network thinking about human origins could transform how we understand identity, ancestry, and human relationships. Rather than seeing diversity as division, we could recognise it as the beautiful expression of ancient human networks that have maintained both distinctiveness and connection throughout our species' remarkable history.

Taking Action: Moving Science Forward

If this research resonates with you, there are ways to support the paradigm shift:

For Researchers

Consider applying computational approaches without evolutionary assumptions to your data

Explore network models as alternatives to tree-based frameworks

Collaborate across disciplines to integrate genetic, archaeological, and cultural evidence

For Educators

Present human diversity as complex networks rather than simple linear progressions

Emphasise the ancient sophistication of all human populations

Help students understand the interconnected nature of human heritage

For the Public

Question simplistic linear models when you encounter them

Appreciate the complex, ancient roots of human diversity

Support research that challenges established paradigms with rigorous evidence

For Institutions

Fund computational research that applies unbiased analytical methods

Support interdisciplinary collaboration across genetics, archaeology, and computer science

Create platforms for sharing data and analytical methods across research communities

Conclusion: Embracing Complexity

The March of Progress image needs to be retired—not because it's politically incorrect, but because it's scientifically inaccurate. Human diversity is far more ancient, complex, and beautiful than linear models suggest.

Network Population Dynamics reveals human heritage as an interconnected web of ancient communities, each contributing its distinctive genius to the broader human story. This isn't a tale of primitive ancestors gradually becoming advanced—it's the story of sophisticated human networks that have maintained both diversity and connection across hundreds of thousands of years.

Moving beyond linear paradigms isn't just about correcting scientific models—it's about embracing a richer, more accurate understanding of what it means to be human. We are not the end point of a linear progression but participants in an ancient network that connects us to the full breadth and depth of human experience.

The computational revolution in human origins research is just beginning. As artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated and our datasets grow larger and more diverse, we'll undoubtedly discover even more complexity in the patterns of human diversity and connection.

But the fundamental insight is already clear: human origins cannot be reduced to simple linear progression. Our species' story is one of networks, not trees; ancient stability, not recent change; sophisticated interconnection, not primitive isolation.

It's time to embrace this complexity and move beyond the March of Progress toward a more accurate, more beautiful understanding of human heritage. The data is leading us there—we just need the courage to follow.

Dr. Ashleigh Davis is an independent researcher applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to human population genetics. Her work on Network Population Dynamics challenges traditional evolutionary models through computational analysis of genetic and morphological data. She is the founder of Ask Lindy Logic Tree technology and Australian Memoirs, and her research represents a paradigm shift toward network-based understanding of human origins and diversity.

Research Contact: ashe.t.davis@outlook.com

ORCID: 0009-0008-8819-8096

Research

Finding groundbreaking insights into human origins today, made possible by artificial intelligence.

Social Media

Connect

info@washpoolresearch.com

+1-555-0123

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Ask Lindy is a new kind of intelligence

For history. For science. For keeps....